***Editorial Note***

My views on Australia Day and the #ChangetheDate movement have changed. My current position on the issue can be seen in the Twitter thread I composed during my involvement with The Familiar Strange public anthropology project (click on the below).

That said, the blogpost below does reflect a position I previously held. So, for posterity’s sake (and as an illustration of how views evolve throughout an individual’s ontogeny) I am leaving the post up.

***

As the date marking the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove passes us by, we have all paid heed to the now-annual calls for Australia Day to be struck down in our national calendar. Yes, this year, like every year, we have heard how the date treasured by lovers of barbecues, beer and Triple J is not “Australia Day” but “Invasion Day” – a date which, rather than commemorating some abiding sense of Australianness instead grotesquely celebrates the beginning of White Man’s colonization of the Great Southern Land.

“January 26, 1788 marked the beginning of a cultural genocide which systematically dispossessed the indigenous peoples of Terra Australis of their land, history and future,” follows this argument. Therefore, its proponents claim, it is a national disgrace to be celebrating Australia Day on that date.

This year among the “Down With Australia Day” pronouncements, a popular video produced by Buzzfeed has been doing the rounds on social media. Labelled “an aboriginal response to ‘Australia Day’”, the video documents the responses of several indigenous speakers who discuss what Australia Day means to them. Celebrating Australia Day, according to several of these indigenous speakers, is “insensitive”; a commemoration of an “invasion”; a day which is “really really sad” for the suffering sewed by British colonists after their arrival.

In principle, there’s merit to some of the arguments advanced in the video. Perhaps a date like Federation Day – that is January 1 – would be a more appropriate date to celebrate Australia Day. For the most part though, the entire production only reproduces viral memetic untruths which add little to serious discussions about “real” issues in aboriginal Australia – like continuing disadvantage in remote-living communities.

It’s a shame, because by regurgitating spoon-fed fallacies about the history and culture of aboriginal Australia – most of which hold no weight anthropologically or historically – it leaves the viewer less informed and the whole debate in a state where only the most reactionary voices are likely to be heard.

The many fallacies orbiting this debate are perhaps best outlined in the form of a listicle. I say this half-ironically, of course, because the shallow analysis which propelled Buzzfeed to the mainstream is at the core of the problem. So. Now. A dissection of some random piece of click-bait I watched on social media – for better or for worse.

Point #1: Sweeping Generalisations about Indigenous Australia

What is perhaps most remarkable about this video is the sweeping generalisations and falsehoods many of its speakers make about Aboriginal Australia. This is even more remarkable because the speakers are indigenous Australians.

1a. “Oldest Surviving Culture”

The first and most obvious fallacy is one speaker’s assertion that Invasion Day marks the survival of the oldest culture on earth. Anyone who has browsed through a tourist brochure selling bite-sized aboriginal cultural experiences is probably familiar with the “oldest surviving culture” claim. But how accurate is this framing?

While aboriginal peoples have inhabited Australia for a long long time (certainly far longer than anyone else), even a cursory examination of what a “culture” actually is shows how utterly ridiculous it is to use a superlative like “oldest”.

Anthropology tells us that “culture” – a term which encompasses the discourses and practices within a given human society – is not static. Rather, “culture” is a continuously evolving set of norms in a state of constant flux – a vehicle in-motion not a petrified fossil. Since culture is ever-changing, ever-transforming, resembling something one day and something else the next, to talk about “aboriginal culture” as possessing attributes like “age” or “survivability” is utterly meaningless.

Of course, quantities we might call cultural “cores” do transmit across generations. Transmissable knowledge (like storytelling and native land management practices) and some aspects of material culture have survived millennia in many parts of Aboriginal Australia. And certainly, where a presiding Aboriginal sense of “being” is concerned, the connection with the past remains important, even if the significance of that connection becomes more abstract as the yawning gap between the Dreaming and the Now grows wider. Be that as it may, when there are tens of thousands of years between cultural forms the differences eventually outweigh the similarities.

In many ways then, talking about Aboriginal culture as being “the world’s oldest surviving culture” is akin to calling the mace carried by the Serjeant-at-Arms of the Australian Parliament “a cultural relic of the bludgeoning instruments used by early hominids in the East African Cradle of Humankind”.

Thus, the point stands that Aboriginal culture today is so utterly different to what it was in 1788 that attributing an age value to any currently-practiced customs and traditions makes little to no sense. (Remember, the destruction of pre-colonial Aboriginal Australia is the reason why Invasion Day is so controversial in the first place)

Moreover, perhaps the greatest irony in this video is the fact that the speakers discussing their “oldest surviving cultures” are wearing European-style business attire and Chinese-made German-branded Adidas T-Shirts, speaking English and talking into Japanese-made video cameras.

With this in mind, there is an obvious cognitive dissonance when people speak about “cultural genocide” and “oldest surviving cultures” in the same sentence. Which is it? Were the first Australian cultures wiped out or did they survive? Granted, it’s not necessarily a binary question – but it’s a question worthy of closer consideration.

Personally, I think that the dispossession of aboriginal people in Australia (which began in 1788) constituted a cultural genocide. As the destruction of the aboriginal population of Tasmania shows, this is a historical reality that would seem to fly in the face of the assertion that pre-colonial aboriginal culture has “survived” intact unto the present.

1b. “They were a peaceful people”/”We are an inclusive people”

According to the young boy interviewed in the video (who, it should be noted, is clearly below the age of informed consent as an interviewee), the arrival of the First Fleet was a day when Europeans came and slaughtered “a peaceful people”.

Apart from the historical fallacy that the First Fleeters simply landed and started slaughtering people on the day they arrived (more on this later), there is a more pernicious untruth to the claim that the indigenous inhabitants of Australia were any more “peaceful” than any other people who have ever lived.

“Inclusiveness” is also used to describe pre-colonial aboriginal culture. But how accurate is this? While most of the aboriginal informants I have come across during ethnographic research in Cape York could be described as both “inclusive” and “peaceful” (for the most part, at least) to claim that either of these adjectives are abiding, essentialising cultural traits is to make a sweeping generalisation without the backing of the empirical record – an over-simplification which borders on stereotype.

Certainly, in pre-colonial Kuuk Thaayorre society, clan rivalries saw the Thaayorre come into almost constant violent contact with members of the Kuuk Yaak language group (“snake speakers”) – a historical enmity which ultimately manifested in the eradication of the Kuuk Yaak as a cultural unit.

No one in the modern Cape York community of Pormpuraaw self-identifies as “Kuuk Yaak” anymore – one is either “Wik-Mungkan” (a language group with strong ties to the township of Aurukun to the north) or Thaayorre. The Kuuk Yaak were literally wiped out. This seems neither “inclusive” nor “peaceful” to me.

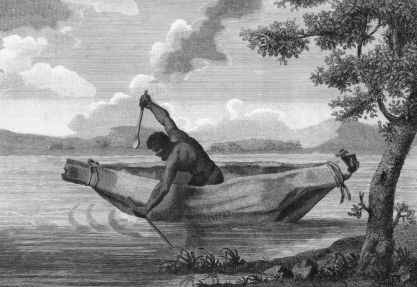

My good friend Peret Arkwookerum (nicknamed “Wookie” meaning “flying fox” – also one of his totems – half Wik-Mungkan, half Kuuk Thaayorre, catching a black bream on his first cast at a sacred site near Pormpuraaw

We know of course, that the interviewees are trying to argue that the pre-colonial Eora of Sydney were “peaceful” and “inclusive” – at least in comparison to the world-destroying British. But even in the case of the Eora, there is little evidence to suggest that they were any less war-like than any other human group that has ever existed.

Incidents of spearing were common occurrences among the natives of pre-colonial Sydney. Disputes were often settled by violence. Under Pemulwuy, a group of aboriginal insurgents gathered to resist (perhaps rightfully so) the settlers occupying their lands. Around the Eora campfires of Sydney Cove, discussions about immigration and the unwanted arrival of the “boat people” were vociferous and heated. Pemulwuy himself was rumoured to have been blinded in one eye in a violent incident with an enemy from another tribe.

Indeed, with all the violence and exclusivity observed throughout the history of Aboriginal Australia it is fair to say that perhaps one of the most remarkable features about Aboriginal people, historically and into the present, is how remarkably like the rest of us they are. Aboriginal people were and are people – and like all societies, pre-colonial Aboriginal society had its racism and its bloodshed, its in-group/out-group-isms and its conflict.

Peace and not conflict is the exception to the rule throughout much of human history. It was no different in the Australia that existed before the arrival of Europeans. To imagine pre-colonial Aboriginal society as having embodied some kind of Utopian dream-state is to cling to the long-since discredited Rousseausian myths of Early Man. It also denies almost everything we know about the evolution of hominids. Namely, that our capacity for violence (if not our propensity it) has deep evolutionary roots – inextricably tied as it to our higher-order forms of social organization and our complex cognition. By contrast, if we’re to persist with this imagined version of a warless early Australia, then we may as well start waxing lyrical about “noble savages”.

Bennelong, an Eora collaborator described by Watkin Tench as “a second Omai”, the textbook “noble savage”.

Pemulwuy. Aboriginal Australia’s most successful guerrilla leader.

Point #2: Excessive Use of the First Person Plural (“We”, “Our”)

One of the common traps we often fall into when talking about the historical lives of our ancestors is what I would like to call “the excessive use of the first person plural”. When one sees historical persons as part of the extended genealogical network which we call “our family” it is easy to start using terms like “we” and “our” in discussions about events that took place centuries ago. Even if we ourselves weren’t victims of what happened to these historical family members, the pain experienced by them is often experienced inter-generationally. In making sense of this phenomenon however, it’s also important to remember that we also possess some agency in how we choose to internalize this pain.

Now, I’m not going to claim that there is no validity to the idea of “inherited grievance” or “intergenerational trauma”. There is significant empirical evidence to support the idea that physical manifestations of hurt can be experienced over and over again by descendants of the initially aggrieved. (New research in the domain of epigenetics is shedding interesting light on this). Nor am I going to deny that oppression and structural violence experienced by members of the same social group can be felt, in real terms, for centuries (and still continues to be felt by aboriginal peoples today). Ancestry is a complex issue which is heavily tied to peoples’ conceptions of their own identity.

Even so, it’s still important to remember that no one alive today was also alive on January 26, 1788, so the loss suffered by the indigenous peoples of Sydney Cove was a loss that no one today actually experienced directly. That hurt, though it might continue to resonate in the present, was transmitted socially – not felt in the flesh. The implications of this factual statement are important when considering reconciliation efforts because the point I am making is simple: even though trauma echoes into the future (usually in the form of memory) there is no reason why the trauma of past others should determine the future.

In a similar vein, some years ago, while munching on a shawarma in a Jerusalem hole-in-the-wall eatery, I listened to an Israeli man prattle on about “how we [the Israelites] suffered at the hands of the Philistines (the pre-modern Palestinians)” – how “they took our land [et cetera, et cetera].” This was why, apparently, “his people” were perfectly justified in wresting the Holy Land back from the Palestinians “all the way to the banks of the River Jordan”.

Naturally, being in Israel and surrounded by heavily armed IDF soldiers doing the rounds through the Old City, my immediate reaction was to smile and nod. Inwardly however, I couldn’t help but think: “Really? Did the suffering at the hands of the Philistines actually happen to you? You personally?”

This point – which pertains to the weaponization of traumatic memory – is a point that the historian Norman Finkelstein has previously brought up in his critiques of the Israeli government’s “Holocaust industry” (a term whose framing I personally disagree with). At what point are we abusing the power of memory by internalizing the trauma of long-dead victims in the present?

In the presence of overwhelming firepower one is inclined to agree with whatever one is told. In the Old City of Jerusalem, some years ago.

There’s no easy answer to this question. It’s not binary – it’s complicated. But from my Jerusalem anecdote, it’s easy to see two problems created when we form overly strong connections with past generations: 1.) it is harmful for conflict resolution and it can perpetuate cycles of violence (as we see in the “who stole whose land” debates in the Holy Land or, say, Yugoslavia) and 2.) it becomes easy to fall into an ancestral phantasm whereby you confuse something that happened to a historical person (who you never actually met) with something that happened to you, yourself.

Of course, I’m not suggesting that the subjugation of the Eora peoples in New South Wales in 1788 is something that has no relevance for a Guugu Yimidhirr person in Far North Queensland in the present.

Events like the arrival of the First Fleet are great examples of the butterfly effect – continuing as 1788 does to generate sociological hurricanes across the continent. A small flap of the wings like the landing at Sydney Cove was the chronological initiator of a centuries-long genocide. History, in this sense, is veritably macrolepidopteran.

Equally, I’m not suggesting that today’s aboriginal Australians should collectively “get over” the dispossession of their ancestors from their native lands. Nor am I suggesting that it is wrong to draw parallels between the historical suffering of Australia’s first inhabitants and the ongoing structural violence directed against aboriginal peoples.

It certainly would be insensitive to tell anyone to “get over” a cultural genocide and it would be factually incorrect to claim that the use of the first person plural in the context of one’s ancestors never holds any weight.

What I am really railing against here is the excessive use of terms like “we” and “our” when talking about historical victims – the inappropriate fusion of past persons with ourselves. I have genetic links to the starving Irish who were loaded onto ships and sent to a penal colony in the Southern Hemisphere. And yet I did not feel their hunger. I am not them – those same Irish.

I have a close ancestral link to Lt Jack Walsh, the first Queensland officer to take a bullet to the head at the landing of ANZAC. And yet, I wouldn’t have the slightest idea what taking a bullet to the head actually feels like. While I do not begrudge other veterans who feel strong personal attachments to the shores of Gallipoli, I claim no real inheritance to the “glory of ANZAC”, whatever that is. I wasn’t there, so that particular battle honour should really have no bearing on my life, my curriculum vitae, and the foundations of my identity.

Similarly, while it is perfectly valid for me to claim that my ancestor the Scottish outlaw Rob Roy McGregor was “one of us” (“us” being “Clan Cattanach”: “touch not the cat, bot the glove”), it would be excessive to claim that everything McGregor lost at the hands of the English was also physically lost by me as his ancestor.

To claim Rob Roy McGregor’s suffering as my own would be akin to claiming his achievements as my own, in a way which conjures up today’s “ugly American” laying claim to “the liberation of France from the Nazis”. Very few Americans alive today can claim this as one of their own personal achievements (see comedian Doug Stanhope tear this sentiment apart).

The past does continue to be felt and heard. But only in the form of echoes. Or through the structures it leaves behind.

3. The Date Itself

Perhaps the most eloquent speaker in the video is the bloke in the red and blue shirt. His understanding of Australia Day, as he describes it, is like “if a guy comes into your house, does horrible things to your family, and says ‘we’re gonna have a party and have a barbie and listen to Triple J on the date we turned up’.”

Leaving aside the debatable use of “we”, if read solely as a celebration of “the day White Man turned up” (a date which symbolically represents the beginning of a cultural genocide), it’s true that Australia Day might fairly be interpreted as a bit “sadistic”.

Again, I agree that there is some merit to the idea of picking a different date to celebrate Australia Day. Perhaps a more neutral date like the date of Federation in 1901 would be more appropriate – given that it doesn’t carry the same historical and emotional baggage as the arrival of the First Fleet.

But to play devil’s advocate, if we as Australians have a responsibility to “never forget” what happened to Aboriginal Australians under colonial rule then doesn’t it make sense to commemorate the arrival of the First Fleet in much the same way that “never again” commemorations have memorialised the tragedy of genocide in Rwanda or South Africa?

Isn’t it a good thing that the counter-cultural “Invasion Day” is dredged up every year simply because of the date on which Australia Day falls? Wouldn’t all the awareness-raising efforts about the atrocities in Australian history fade into obscurity if the PM just went and changed our national day to the whatever-th of July?

Similarly, if one is being faithful to the historical record, one should also acknowledge that January 26, 1788 most certainly was not the bloodiest chapter in the history of European colonialism in Australia. There were no slaughters or massacres carried out on the day of the Sydney Cove landing.

Arthur Phillip didn’t simply arrive and begin slaughtering (though his miscreant gamekeeper would later develop a horrible proclivity for that).

According to my reading of history, the actual “invasion” – the very first boat landing – was actually a few days before January 26 anyway. The 26th was merely the date when the colony of New South Wales was formally declared. Compared to some of the other dates in the colonial history of Australia, January 26 was comparatively tame.

Australia Day does not commemorate, for example, the date of the first landfall made by Europeans on Australian shores – June 1605 – when the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon, made the first contact with aboriginal Australians at Cape Keerweer – a contact which was characterised by the massacre of “savage, cruel, black barbarians” who had slain some of Janszoon’s sailors.

Neither does Australia Day celebrate travesties like the Black War in Tasmania, part of which involved the formation of an extended line by the 63rd Regiment to corral Tasmanian aborigines into a penal colony on the Tasman Peninsula.

Certainly, while the landing at Sydney Cove did mark the beginning of colonization, the date of the landing itself – January 26, 1788 – was a pretty low-key, native-friendly event. Per the accounts of Watkin Tench and others, the amicable relations between aboriginals and settlers continued peacefully for at least the first year until the Governor’s game-keeper, John McKintyre, started slaughtering Eora for fun on his hunting parties -resulting in his own death at the hands of Pemulwuy.

Of course, in downplaying the symbolic importance of the 26th, I’m not seeking to revise the history of the First Fleet’s arrival by painting it as a harmless event in our nation’s history. It may have been the contingent event upon which modern Australia was founded but that doesn’t make it something to be overly proud of.

More than that, what I’m not calling for is an Andrew Bolt version of Australia where Aboriginal people just move on from the wrongs done to them and “pick themselves up by their own bootstraps”. Nor am I advocating for any particular position in the discussion over who gets what in modern Australia – the ins-and-outs of Native Title and reparations still need some work.

What I am calling for is a little bit more intellectual honesty in the way we discuss the past. Yes, the colonisation of Australia and the dispossession of its native peoples was a travesty of genocidal proportions. But no, the First Fleet did not land at Sydney Cove and immediately begin “slaughtering” people in droves (as the Buzzfeed video incorrectly claims). No one was killed or poorly-treated on the 26th.

Likewise, while aboriginal Australians have inhabited Australia for a period dating back at least 50,000 years, the heterogenous Aboriginal cultures of today are “not the world’s oldest surviving culture” because the very idea of an oldest surviving culture is a load of anthropological horse-shit.

(And anyway, what about the uncontacted peoples of the Orinoco basin or the grumpy resistant-to-contact North Sentinelese? These groups continue, for the most part, to live in the isolation they created for themselves many thousands of years ago.)

Ultimately, it’s worth emphasising that the video was produced by Buzzfeed (under the watermark “Buzzfeed Aboriginal”) – the internet’s classic purveyor of clickbait-for-profit. So perhaps it is not really worthy of serious intellectual consideration. At the same time, the video still speaks to an increasingly-popular discourse and it has had an impact – purpose-designed as it is to emotionally-manipulate us into sharing and spreading (not unlike war-prop videos produced by ISIS or the Lions of Rojava in Syria). And yes, sharing and spreading is something that many all over my Facebook newsfeed have certainly done… by my last count this video has 2,082,458 views.

Indubitably, the white demographic of the video-sharers is worthy of note. Conspicuously absent from the re-share meme-train are any of my aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander friends on Facebook – probably because they are too busy catching barramundi or counting crocodile eggs with the Indigenous Land and Sea Rangers program. Or doing other, more useful things… like protecting the country.

Wookie examines one of his totemic ancestors (“minh pinch” is the Kuuk Thaayorre word for “crocodile”)

As for me, while my aboriginal friends are out fishing and drinking beer on Australia Day lapping up some or other gorgeous Cape York sunset, I’m writing this from the cold depths of wintry Canada. This 26th, I’ll be spending the rest of the day dreaming of barbecues, thongs, beaches and Triple J.

After that perhaps, I’ll be waiting out for ANZAC Day – sharpening my pencils for the annual debate over whether the remembrance of the landing at ANZAC constitutes a day for the mourning of dead sons or a day when Australians unite to glorify bloodshed and violence. Probably, ANZAC Day (like Australia/Invasion Day) is a little bit of both – a celebration for what we have and a remembrance of what we have lost.

Sunset over the Gulf of Carpentaria in the Western Cape York community of Pormpuraaw. Reminds me very much of the Aboriginal flag.