Sunburnt, thirsty and four pitches from the summit of Kaga Tondo, I look up at the blank wall above me and despair. I have been climbing for the better part of two days now, a cumulative total of one thousand metres of rope-soloing and jumaring in the burning heat of the Malian desert.

Even in the shade, the temperature is thirty-five degrees. Beyond on either side, the sun blasts the rock like sculptures in the kiln. My roasted nape is hot and blistered, the once-pink flesh transformed from medium-rare to a dark and well-done.

Without let, the climbing has been sustained and constant – dead vertical to overhanging – and now, just shy of the top, I wonder if I can really do this. I am four-hundred and fifty-metres up the North Pillar of Kaga Tondo, the index finger of the Hand of Fatima massif, the tallest standalone sandstone rock tower on the planet.

Perched upon “La Brèche“, a five-metre by two-metre platform between a free-standing gendarme and Kaga’s summit headwall, I am utterly spent and all alone. Maybe out of my depth.

The next pitch is the hardest pitch of the entire route. At 6a+ in the jargon of the French rating system it is not particularly difficult for me when climbing out of the car – but now, severely dehydrated with spasming muscles, it seems impossible.

The rock is sleek and mostly featureless – the good holds separated by sections of run-out traversing blankness. Nigh-on impossible to protect a fall save for a few tiny horizontal breaks and a single rusty piton, hammered in-situ. The crux of the pitch, the most difficult section, will bring me up eight metres above the ledge without a single piece of protection (enough to break my legs in a fall) and then left and out above the void. Nothing below me but a sickening drop – half a kilometre, uninterrupted to the ground.

After two days in the heat with the bare minimum in water, I am approaching the margins of control. My arms are spent. My brain is fried. Of the six litres I had started with, I’ve now only eight sips left. Eight sips. That’s it. Two sips per pitch to get me to the summit and the thirsty bivy that awaits. Nothing for the descent.

The descent… the descent.

Fully-committed now, I dream of that fucking descent. Down the West Face, accessible only by the summit. A summit that is reached by traversing across and up the blank headwall above me. Do or die.

They call this pitch “La Voie Pujos“. Named for French mountain guide Alain Pujos – one of the massif’s early explorers. According to the history books, Pujos was a talented climber – among the best of his day. And yet. And yet, one sunny February day, after setting out to free-solo the shady North Face of Mt Hombori, Pujos reached the summit, sat down next to a rock and died. It was the dehydration that got him. He’d simply climbed himself dry.

I’d been stewing on this the past two days – the historical fact of Pujos’ untimely end filtering through the bottleneck every time I took a sip.

I look to my right at the other digits of Fatima’s hand – Wanderdu and Wangel Debridu, the stumpy middle fingers; and Suri Tondo, away and across the plateau, the broadest of the summits. Together with Kaga Tondo and Kaga Pomori (the slender thumb, out of view) they form a rock massif, which when silhouetted dark and brooding against the setting sun resembles the venerated icon known across North Africa as “La Main de Fatima”.

The Hand of Fatima with the setting sun behind

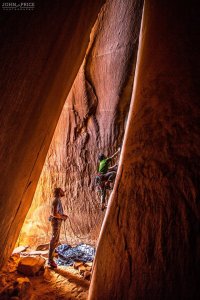

Looking up at the smooth final headwall of Kaga Tondo from La Breche

“You wanted this,” I mutter to myself, tongue dry, throat parched. It was true. I had wanted this. I’d wanted to be here so badly that I’d made two attempts in less than two years, packing a heavy bag full of ropes and climbing equipment and muling it solo halfway across the world. All that, just to get myself up a giant rock in the middle of Mali.

“You wanted this,” I mutter again.

I go through a quick inventory in my head. I’d finished my bag of dried mango yesterday afternoon and feasted on the can of sardines that Suleiman had packed me the night before. Saving the bread for my breakfast this morning had been a bad move. It was already stale – at least three days gone – at the time of purchase. Dry and floury, it had given me cottonmouth. A few bites were all I’d managed.

What I really needed though was water. Water, water, precious water. After these eight sips, there’d be nothing left. I look up again at the summit headwall. A trio of birds surf the air currents, suspended in nothingness. Suddenly a black swallow, wings tipped with flashes of fire-like orange dive-bombs through the breach above my head, skirting along the side of the cliff before disappearing around the corner. I think back to my first solo climbing experience, in a similar precarious position, halfway up one of the cliffs of Mount Arapiles.

The day is at full bloom and the yellow wheat fields of Wimmera shimmer on the horizon. I’ve spent the morning in the shade on Dunes Buttress, methodically working my way up the direct route. Tracing a path over a slab, beyond a little ledge and up towards the summit – seizing this beautiful line in my fingertips. There’s a recurrent theme in the route-log here – “Arab”, “Saracen”, “Lawrence”, “Dunes” – all the names whispering of sandy somethings in faraway desert-scapes. A fine place to be lost in geologic time.

On the third pitch, hanging from a web of metal contraptions, a breeze blows across my nape. I move away from the belay and, pulling over the lip of a little rooflet, I scan the rock above for a good hold. Where the eyes see little, I feel around with hand and fingers, leveraging my tactile sensors in the search for something positive. Still, I clutch at nothing so, pausing, I reassess and remind myself to enjoy the view.

A robin whizzes by. A rotund, little scarlet thing – bobbing up and down with each flutter of its wings. Like a breast-stroking fat man trying to stay afloat.

Below, the shapes of a few climbers on neighbouring buttresses. The familiar sounds of “on belay!” and “safe!”.

Here though, on this patch of rock, there is quiet. There’s no call-outs on a solo climb. No commands for more or less rope. No laughter. No sound. Only the climber, his rope, rack, the rock and an inner monologue – a monologue dithering between the fear of loneliness and the bliss of silent solitude. No miscommunication, only an error of judgement. No waiting for your second, only idling. No one else to blame – only the self. Everything is in my hands.

Thus, alone on Dunes Buttress, I pause for a second longer, feed a handful of slack through my belay device and reach out higher, higher, higher – piano-fingering at a distant hold. With tenuous approval, it accepts my grasp.

I ee-adjust my right foot now, swinging my heel high onto a tiny horizontal ledge. The rubber finds purchase and I rock my weight over. I climb. A few more metres and I emerge into the sunlight at a place called “the Oasis” – a heavily vegetated ledge two thirds of the way up. It hides a little cave amongst the debris of fallen spires, lush by comparison to the rest of the buttress. I set my belay and rappel down to retrieve my pack and gear.

As the sun reaches its zenith, it disappears behind the summit and my route is soused in shade. Jumaring back up to my belay, I pause for a muesli bar on the ledge, drinking in the near-eastern vibe up here. Luscious life hidden amongst red, sun-roasted rock. It could be an oasis in the Sinai, Palmyra, Azraq. I miss that part of the world.

I continue on, moving quickly now that the sun is gone, recharged by a muesli bar and a sip of water. I clamber over a roof and traverse right over a finicky corner crack.

A few moves later and I am standing beneath a bulge of smooth rock. The summit lies just beyond. My hand feels for a positive edge. I seize the hold and place a cam. A fall here would be long and unpleasant. The top is no place to die. I pause again, counterbalanced on one foot, one hand in the chalk bag, the other attached to the cliff. I crane my head, left and right – complete exposure, nothing but air all around me. For a moment, I smile. I realise that I am happy. Alive as never before.

Emerging into the sunlight, I look up into the cloudless sky. I’ve company. Two peregrine falcons flying wing-to-wing, silhouetted black against the burning orb. Everything seems perfect – the summit, the sun, the birds, the final move. I stand on top and hoot a victory hoot, drinking in the experience. A rope-solo of Dunes Buttress. Nothing noteworthy at all, really. People go ropeless on this thing all the time. Still content, I pick my way down towards camp.

Two years of marking time. Calendars filled with study, work then travel. I find myself in Mali. Once again. This trip has been a long time coming – an allotted few weeks carved out in the gap between postgraduate research and moving to the other side of the world.

I drag my bags to the front gate of The Sleeping Camel in Bamako. The lobby is bustling. The usual kinds of foreigners one expects to find in a country in the midst of a civil war. A Swedish freelance journalist tapping away on her laptop. A pair of Dutch police officers seconded to the UN. A crew of British military de-mining contractors with not a word of French between them. Hordes of aid workers belonging to a whole menagerie of development agencies. A loud-mouthed African-American with mining interests in the Congo. Like a caricature, he walks around in a scarlet velvet jacket. A rogue’s gallery of expats-in-Africa stereotypes, this lobby.

Then, of course, in the corner courtyard of the compound, the slightly-insane German quintegenarian camped out beneath an army-issue groundsheet under a mango tree. He ports a long grey beard and a karakul. He’s ridden here by motorcycle from Munich, he says. On a journey “to find the kingdom of Heaven”

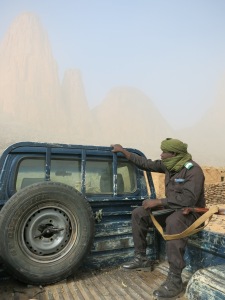

Next morning I check out, board my afternoon bus to Hombori and settle in for what is sure to be a long and bumpy ride through the night. We pass Douentza at first light and the distant shape of the Bandigara escarpment glows black against the changing sky. We have entered “la zone d’urgence” – what the Malian defense ministry has deemed “the dangerous north”.

I’d first visited Mali the previous June, six months after Islamist extremists in the dunescapes of the Sahara had taken half the country. They came from the north – black turbans, indigo veils, severe expressions, touting freshly-oiled Kalashnikovs looted from vaults of Gaddafi’s sprang-open armouries. From their refuge on the Algerian-Malian border they struck out across the desert, riding the wake of a nationalist uprising amongst disaffected Tuareg nomads. They hit Timbuktu, the age-old desert oasis once the centre of Islamic teaching, with rifle and whip. There, they set to the task of destroying the tombs of Sufi saints and thousands of medieval tomes. Idolatry, they called it. Nothing the world hadn’t seen already from the denizens of jihad.

Gao, Hombori and Douentza. Three key towns on the road south were the next to fall. The ill-equipped Malian army was driven out. Tourists kidnapped, murdered. Adulterers stoned. The standard narrative when jihadists come to town. Needless to say, the foreign tourism industry was wiped out. In the towns they captured, the jihadists instituted a juridical order based on the strictest interpretation of sharia. The reduction of the north of Mali into a war-torn hellscape was instantaneous and total. Northern Mali had become yet another sunburnt Sahelian sore.

This sign perfectly captured Timbuktu, 2013. A sign warning travelling cameleers of the dangers of AIDs, the faces of the camel and rider spray-painted over by the djihadistes during their reign over the town

A few months before my first tour of the country, the French had arrived to take the north back. Operation Serval had moved quickly, rolling toward Timbuktu with a rapid mechanical fury. One-by-one the towns at the edge of the desert were reclaimed. The occupying djihadistes fled and the Gallic offensive continued. Airborne assets in full swing, the French brought the fight hard and fast against the enemy, right to their desert sanctuary in the Adrar des Ifoghas – a complex natural labyrinth of canyons and sandstone bitter from which they had launched their war.

Then, like djinns at dusk, the jihadists had disappeared into the sands, packing up and shipping out almost as quickly as they had arrived. Onwards to Libya. To regroup. With the Islamists scattered, and the nationalist fury of the Tuareg temporarily restrained to a grumble, the French had done a decent job. Now, the harder task – winning the Long Peace – lay ahead.

This was the hard part.

Since Serval, suicide bombings and roadside ambushes had become the mode du jour in all the former tourist hotspots. All across the north, gunfire could still be heard at night. Mali was anything but a safe country.

2013 found me at the house of one or other of the European explorers who “discovered” Timbuktu.

But something was drawing me. Something big. The Hand of Fatima. Five sandstone rock towers, arranged like the fingers of a mighty hand, rising out of the desert. Two hundred kilometres from Timbuktu and a long way from anywhere else. It was like climbing in a different galaxy – extra-planetary wall climbing.

Since 2013, following my first trip to Mali, I could think of nothing else.

That trip had been an adventure in itself. A summer hike through the Dogon villages at the base of the Bandiagara Escarpment had seen me go down with heatstroke in fifty-five degree heat.

Later, a visit to Timbuktu had culminated in a breakdown on the return journey. A waterless walk back to the next town. Sips of water-tasting-of-battery-acid siphoned from the engine.

A carte-carte on the border crossing from Burkina Faso into Mali.

A Fulani woman, clad in hijab, publicly breastfeeds in the back of a carte-carte. Islam (and its rules of modesty) is very syncretic in West Africa.

A typical hellish day during the Sahelian summer. The harmattan blowing from the south.

The view of the Dogon villages from high on the Bandiagara Escarpment. The previous inhabitants of the area – the Tellem Pygmy – built their quarters high up in the cliffs crafting tiny doors and miniature windows as portholes looking over the world.

A typical mud mosque in Dogon Country at the base of the Bandiagara Escarpment.

All packed and ready for a failed expedition

A vehicle breakdown on my return from Tktu after some ethnographic fieldwork. The breakdown culminated in…

… a long, long walk

This time though, leaving Bamako in the late afternoon to travel through the night, I was Hombori bound – on the road to my final destination, the Hand of Fatima massif. The sun rises slowly, a shy new dawn.

The bus stops in a small village near Boni and with the sun poking its nose above the horizon it is time for fejr prayers. Ahmed, the Malian soldier in the seat next to me shoulders his rifle and steps outside. Behind him, two brown-robed Fulani men, dressed in bone-white turbans. Conducting wudu, the ablution of washing, he touches the red earth with bare hands. Pensive, methodical, thorough – he cleanses his body with the dust. One of the enturbanned men leads the prayer and they line up, performing their raka’at, facing the rising sun.

The bus carries on into a clear desert morning – onwards through a scene ripped from a pictogram of the Old West. A clear day, a blue sky, citadels of red rock in contrast with the starkness of the plains. With every passing castle of rock, a dozen more appear on the horizon, the scrubland between each buttress teeming with desert life. A trio of camels, drifting across the road. A goatherd and his servres, moving between the thorntrees of a sparse, dry brousse.

And finally, growing out from a horizon of nothing – les Aiguilles de Garmi – the famed Hand of Fatima – a five-fingered escarpment of vertical sandstone. The summits reaching skywards, backlit by a blazing morning sun.

As the Hand comes closer, the contours of its rugged cliffs become clearer – palisades of rock formed from the compaction of millions of years of shifting sand. In the summer heat, the blasting harmattan, the waves of conquering armies and the ravages of recent war, the massif has remained aloft, uncaring, indifferent, a sentinel unto itself. A rocky hand raised, open-palmed. Fashioned by some geologic Lah.

Dost thou not then believe? he’s saying.

Wangel Debridu, flanked by Kaga and Wanderdu, encircled by an angelic halo of light

In all, the Hand of Fatima comprises four rock towers, with a fifth subsidiary rocktower Suri Tondo (Suri being a man’s name and tondo meaning “rock”), sometimes included as a fifth finger – a polydactylous pinkie on the far end of the plateau. After Suri, there is Wanderdu (“wheat” in Fulani), the ring-finger; Wangel Debridu (“the pregnant woman”) the middle finger; Kaga Tondo (“the grandfather rock”), the mighty index finger; and Kaga Pomori (“the grandmother rock”), the escarpment’s thumb.

In Fulani, the etymology summons the home and hearth of an ancient metamorphosed family – Suri the farmer, his wheat field, Suri’s pregnant wife, his father, the wisened Kaga and the grandmother, Pomori, wife of Kaga.

Throughout much of the Islamic World, the “open hand” is palpably culturally significant – sometimes referred to in Arabic as “the khamsa” (Arabic: خمسة, literally meaning “five”, as in, “five fingers of the hand”). In North Africa in particular, especially Morocco, the “khamsa” has been co-opted into a popular palm-shaped amulet – an open hand inset with an eye – worn by pregnant women as protection against the evil eye.

The five fingers of the Hand of Fatima massif. From left to right Kaga Pomori, Kaga Tondo, Wangel Debridu, Wanderdu and Suri Tondo

The “khamsa” or Hand of Fatima

Certainly, it seems, for the inhabitants of Garmi and Daari, the two villages spilling out from the base of the massif, the mountain has played the role of protector. The djihadistes never stopped there, I’m told as I leave the bus. The rocks were too intimidating and they never lingered long in the area.

As the bus takes off down the well-holed road, I am left alone with two and a half packs of gear. Two children emerge from a small shelter in the distance – a dome tent-like structure made from sticks. Fulani hut.

Children are always the first to notice changes in their environment, always the first to notice a newcomer, the first to greet an outsider.

They dance around me with happy smiles, laughing and nattering. I understand nothing. A woman emerges from the stick shelter, shouting after the children. Then, noticing me, the strange white man with more bags then he can carry, she pauses.

Even though she spies my ropes and knows me a climber, she looks confused. Why am I here? Now? With things the way they are in the rest of the country?

I’m extrapolating here of course, because without a common tongue, I understand nothing she says. Maybe she’s just wondering why I’m stood on her front porch.

Locals in the village of Daari chatter in Fulani, gathered outstide my stick-built tent

Children are gathering in greater numbers now and in the distance I hear the sound of a moto, fanging down the highway. A thin man in an FC Barcelona jersey arrives. Messi jersey of course.

“Bon matin,” he says. “Ça va?”

At last! Someone who speaks French.

“Ça va bien maintenant,” I say, emphasis on the going-well-now part. “Tu parles français et ça me fait plaisir.”

He nods. “Oui, the people here in Daari,” he says. “They do not study at the school. But over there in Garmi-” he points to the shoulder of the massif, and a narrow rocky path leading off to the left of Kaga Tondo, the index finger. “-we all speak French.”

With meals and a village of French speakers less than a kilometre away, it doesn’t take much for Sooleiman to sell the idea. I should stay with him.

Sooleiman, le grand cuisinier

Curious kids in the village of Garmi

Children in Garmi pose for the camera

The next two days are used to scout the area, recceing the possibilities, stringing along Amadou, the son of the village chief of Garmi, as a walking guide around the massif.

On the second day, Amadou and I team up for an ascent of Mariage Traditionel (6a+), the classic line on Wanderdu, the stumpy ring finger of the massif.

As a boy, Amadou was taught the basics by Salvadore Campillo, a Spanish mountain guide who lived twenty years in Daari. The climbing with Amadou goes along well.

At the belay ledge of P2 Mariage Traditionel (6a+), Wanderdu

Amadou stems his way to glory on the final crux pitch of MT

Amadou on the Deuxieme Terrasse of Mariage Traditionel

After lunch and a long guzzle of water during the hottest part of the day we scout out the other possibilities. Foremost in my mind is the route that has become a two year obssession for me – the “obscure object of my desire”. The region’s most striking line.

Towering six-hundred-fifty metres above the Sahelian desert, the North Pillar of Kaga Tondo. A red sabre of perfect grès. A well-ledged yet flawless line following a series of gendarmes up the world’s tallest stand-alone sandstone rock tower. In the literature, both oral and written, it is known by many different names – “l’eperon nord”, “l’arête nord”, “la voie Pujos”, but the locals know it only as “La Grande Voie”.

In their guide to the greatest big wall climbs on Earth, well-known French climbing pair Stephanie Bodet and Arnaud Petit say of the route – “une voie incontournable sur un sommet unique, sans contestation parmi les plus belles grandes voies longues et adventureuses de la planète”. Basically, it’s pretty fucking rad.

A climb of the North Pillar would bring me to the highest point of the massif, the descent requiring a traverse across the summit and a long chain of abseils down the west face. As we pass beneath Kaga, Amadou points out the fall-line. He’s never climbed the peak himself, but verbatim, he describes the specifics of each ledge and rap-station.

I walk away content with what I’ve learned. The reconnaissance, I’ve come to realise, is just as important as the climb’s execution.

As in war, where information transmitted from a forward observation post is critical for an army’s “intelligence preparation of the battlespace”, the penchant for scoping the lines and descents of a big wall with eye and spotting scope are what gave the great wall-climbers of yesteryear – Robbins, Bridwell, Ewbank, Chouinard – the chance to succeed on their own “impossibles”. The Salathé,

the Sea of Dreams, the Muir, even the Totem Pole. All scaled from afar for their first time.

Now with a recce of the all the approaches under my belt, I know that a point-to-point traverse of the Hand of Fatima is also possible. Starting in Daari, following the North Pillar to the summit of Kaga Tondo and descending to Garmi. All as part of one great knowledge-seeking expression of movement.

The village-to-village traverse idea came from a common interest in both horizontal and vertical movement – moving from A to B via a beautiful mountain summit. Ever intrigued by human migration, the idea of linking population centres via an aesthetic mountain summit had always appealed. Kilian Jornet’s

“run” from the Italian village of Courmayeur to the French town of Chamonix via Mt Blanc’s Innominata Ridge could be held up as the immortal standard for a point-to-point traverse of this kind.

My planned village-to-village traverse of the Hand of Fatima massif

Crushing the wheat grains in the village of Daari. The fine powder is sometimes mixed with sugar, water and goat’s milk to make a delicious thick health drink. In the distance, “La Breche” can be seen between the final gendarme and the summit of Kaga Tondo.

Kaga Tondo from Garmi

My grand traverse project would bring me from the old climbers’ camp in the village of Daari to my cosy abode in Garmi. There, shade, sleep, food and most importantly, water, would await.

Content with my reconnaissance, I put my camera away and trot off down the trail, ghosting Amadou on a circuitous track through the boulder-fields at the base of the mountain.

Walking back to Garmi in the dying sunlight, Amadou recounts to me the myths of the area. Unlike the stories told in other mountain ranges where I’d climbed, the Hand of Fatima seemed to have a rather confused mythological history.

Indeed, much like the history of the region itself, with its mixing of cultures and its syncretic brand of Islam, the story of the massif is an assembly of scattered tales – a tapestry woven from many threads.

One tale figures the massif as the hand of some primordial woman – an outcast who, as she lay dying in the desert, reached her hand towards the sky. The rest, they say, was consumed by shifting sands.

Another tale tells of an ex-cannonical pilgrimage by the Prophet Mohammed – who, in no short order, named the massif after the dainty hand of his favourite daughter.

Where the imagery of the hand is concerned, others contend, it was the French explorers, reminiscing on the khamsa amulets they had seen in Moroccan marketplaces, who were the progenitors of the name.

And finally, there is the myth of Suri and Fatima – the tale which seems closest to the original local story.

“Fatima was a young girl,” Amadou tells me. “She would hunt the animals of the escarpment with her father. When all the animals were hunted, Fatima and her sister began climbing the cliffs to take the eggs from birds’ nests. One day, she fell but catching her hand on a crasse in the rock, had it severed. When a wandering marabout asked where her hand was, her father, Suri replied, rather that it was there – the five fingers of rock dominating the skyline above the village.”

The glove fits, I muse, reflecting on that final story as I fall asleep that night.

Inquisitive kids in the village of Garmi

Sooleiman’s sister, Fatima

At five a.m, I hear the rumble of Amadou’s moto. In the distance, beyond the mudbrick walls. Supine but with eyes open, I peek up at the gaps between the metal shutters. Beams of approaching headlights refracted across the room.

As a méhariste waking to the sound of approaching camels, I know that this, my transport away from safety, has arrived.

My bag already packed, I down half a litre of water, stuff an orange in my pocket and mount the moto behind Amadou. Together in the pre-dawn darkness, we take the pot-holed, bombed-out highway to the other side of the massif. Reach my starting point. The old climbers camp.

Kaga Tondo, profiled darkest black and in grisaille, towers above us. We pick our way up the boulders to the base of the éperon nord.

From Amadou, I relinquish three bottles of water – five-point-five litres sum total. I shake his hand and bid him farewell. The last person I will see for the next two days.

I charge up the opening pitches, leading, fixing, cleaning, jumaring, reaching the first terrace at daybreak. Check the watch. If I want to be off this thing in two days, I need to do every pitch in about an hour. I’m slower than that.

“Just flattening out the speed bumps. Just getting the system dialled again.”.

Climb another pitch, return to my bag and guzzle some water. The early morning sun burns hot and bright and I retire to a pocket of shade. Devour an orange. My mouth is already dry. Another long pitch leads me to the base of a chimney and I look at my watch again. I check the topo and confirm my position.

I’m moving too slow. This route is going to take me two and half, maybe three days, at least. I have five litres of water left in my pack – one-point-seven per day. A survivable ration. But barely.

I do the math again, hoping I’d been too pessimistic with my first set of calculations. The math is good, my figures right. Continuing the push is going to bring me to the edge of thirst.

I look at my watch again.

Looking at your watch isn’t going to make you climb faster!

Sunrise on Kaga Tondo

Racing up the opening pitches

Lovely view of the Sahelian plains from the first terrace

Jumaring, Icarus-like, into the burning sun

Back to the awaiting pitch. A loose, blocky, flaring, squeezy horror chimney. The kind of pitch that makes you happy you remembered your helmet. The kind of pitch you send your mate up on the sharp end to suss out the death-potential.

I’d heard the faintest whisperings from the villagers in Garmi that “la Grand Voie” had once been free-soloed. I couldn’t comprehend it. Most of these holds looked like they would rip at any minute. A vertical sand dune. Not unlike the choss you’d find on the

Dog Wall in the Blue Mountains. Pure misery. Though misery, I suppose, is what it’s all about.

In the end.I pull a few metres of slack and commit to the looseness.

Don’t fall, don’t fall, don’t fall. I’m through.

On two good ledges now, I spread my legs into a stem, suspended like a gymnast above the sickening void. Snap a photo, continue up to the belay.

Looking down at the horror chimney

A pitch or two later and I reach the base of the first gendarme. Typical for multi-pitch sandstone, the way up the North Pillar does not take a clear path up a series of corners and cracks, but wanders hither and thither across an arête of red rock, winding a way skyward like a snake coiled around a caduceus. Route finding and not the climbing, is the crux of this voie. Per Bodet and Petit.

The next pitch is a traverse. Then a series of roofs – one, two, three – to the ledge above. The French, on their topo, call the pitch the “traversée aérienne“. In elite French alpiniste speak: “terrifying shit for mere mortals”.

The Petit-Bodet topo I had with me.

Departing my perch, I quest out onto the pillar’s exposed face, finding that indeed, this pitch involves some sketchy, terrifying shit. Uncomfortably long run-outs above questionable protection.

At the crux, on the lip of the third and final roof, I pause for a time, dilly-dallying to see if there’s an easier option. Difficult to tell.

Fuck it, there’s a good handhold higher up.

I commit to a

“deadpoint”, throw for it, stick it, cut loose with both feet and continue climbing.

That felt pretty heroic.

I fix the rope and get ready to clean.

The sun lowers in the sky. It drops behind the massif, sousing the North Pillar in shade. The shadows of Fatima’s fingers creep across the desert plain below, the dark, nebulous digits slithering over Daari. Protection from the evil eye, watching over the village.

In the dying light I charge up some blank, black slabs. Making the most of the cooler hours. And my dwindling water supply.

Fixing two pitches, I return to bivouac on a broad and comfortable ledge. The ledge is encircled by a small stone corral. The work of unknown climbers-by.

The pitch before the bivouac ledge

Bivouac ledge selfie.

Suffer.

Night falls. I procure a nut-tool from my harness. My spoon tonight. A tin of canned chicken is consumed. Then a can of sardines à l’huile argan. I learn that olive oil is not nearly as refreshing as a bottle of chilled water. A bivy ensues. I toss and turn, thirsting some.

The following morning I pack my bag, sip some water, and jumar into a racing dawn.

I run it out in the interests of speed. I reach a sloping ledge – la terrasse inclinée in Bodet and Petit’s topo – turn an exposed columne aérienne and am welcomed to the pillar’s upper third by a howling wind.

I look at my watch again, feeling a rising sense of urgency. The sun is high now and it will soon be on the descent, the route now totally swathed in shade. Below on the plains, the mighty shadow of Kaga Tondo lengthens over Daari. Same as yesterday, with its crescive forcefield.

I move. I thirst. I climb. Then, finally, from my perch in La brèche, I look up at the crux pitch and the final one hundred and fifty metres of the North Pillar of Kaga Tondo.

Dinner

La brèche

I despair, yes, but all too soon I am left with only my rope, my rack and a ticking clock. I commit to the traverse. Up the blank wall, crimp, crimp, smearing with my feet, the rubber on my shoes scraping desperately to find purchase on the smooth rock. My footwork is rubbish, like a stumbling drunk. I’m still attached though – somehow – and I reach a horizontal break, plug it with a wobbly cam, and continue questing out left.

A howling easterly blows across a smooth face and the heat of a setting sun nips on my red-raw neck. I reach the anchor. Carry out some “unorthodox” back cleaning for expediency’s sake and lower out into the void.

The crux pitch traversing left and up and away from La brèche

Getting high on the North Pillar of Kaga Tondo

The next pitch is a hand-crack splitting the headwall, shadowy fingers lengthening across the plain beneath me. On autopilot now, the despairing gone, committed to the shadows. Handjam over handjam, feeling like Webb in the English Channel, swimming towards the summit, swimming towards victory. I am going to make it. I know it. The crux is way down below, a mere memory beneath my shoe rubber.

Darkness approaching. Swiftly.

I reach a large broad ledge, traverse right, stem up the final corner and fix the final pitch. I scramble up a pile of boulders, ripping the metal accoutrement from my harness and sprint to the summit bloc, eager to scope the sunset and descent before the dying of the light.

The shadow of the massif over Daari. The wall of the destroyed camp seen below.

Summit of Kaga Tondo

Summit. And broadside, first rappel spotted.

I love the smell of aluminum in the evening. Smells like, survival.

The wind howls. The sleeping bag comes out. I feel the cold of a stark desert night. I thirst. Away and in the darkness of the plains, I see the diesel-powered fairy lights of the French military base. Directly below, the glowing red dot of a solitary campfire. Some nomad, who, like me, is up for another night out. Another waterless summit bivy –

the second waterless bivy in as many weeks.

It is New Year’s Eve. 11:59am. The clock strikes midnight. January 1st is my birthday. Somewhere on the other side of the world my girlfriend is probably cosied up in front of a movie and my mates are downing cold ones on the beach. My parents are having an early one. Not me.

“Happy birthday to me, happy birthday to me… Fucking idiot”.

I roll over, miming sleep.

Sunrise. A tricolour sunrise. Red, white, and blue. The French flag to greet me this morning. Liberté, égalité, fraternité. Away and down on the goudron, a truck rambles along, its gleaming headlights shining like a beacon of hope through the darkness. With this, the harbinger of the new day, I feel good – like I’m going to live. Even in my dehydrated state.

Papery skin and dry retinas. A thirsty bivouac.

A tricolour sunrise. Red, white and blue. The headlight of a camion on the left.

Descending from the summit of Kaga Tondo

I begin my descent, thirsting hard. It seems like days since my last drink.

“Keep going. Get down. Think about what you’re doing.”

I reach a notorious abseil station, a nasty crack littered with the rap tat from one of Salvadore Campillo’s abseil disasters. I clean up his mess but then encounter the same problem on the same pitch.

Stuck rope.

“Dammit!”

I can’t re-climb it so I cut my rope, using Salvadore’s rope in conjunction with what remains of my own. The next abseil doesn’t quite reach the next abseil station – I only have enough rope to get to a small stance above it. There aren’t many spots for another abseil anchor here – it’s a blank face. I could jumar back up but I need to get down. I need water. Desperately.

Fuck it.

I pull the rope and eyeball the ledge below me. It’s wide and broad with good run-outs either side even if I missed my mark.

“You’re not thinking about that are you.”

“You can make it…All those parkour videos you watched as a teenager, looking for things to do in your urban jungle…”

“No way. If this was a guide’s exam you’d have definitely failed.”

“It doesn’t matter… get down.”

I jump. I stick it. There was never really any doubt. But it was a stupid thing to do.

“This is some crazy shit..”

In my dehydrated state, my judgement is definitely skewed.

“Don’t do that again!”

I need to keep moving. To keep making decisions. To keep doing. Water. All I want is water.

Looking towards Suri Tondo soused in the early morning light.

The first abseil on the descent down the West Face

Enter Amadou. He is waiting for me at the base of Kaga Tondo with a backpack full of water. The first person I’ve seen in two and a half days.

“La grande voie,” he says to me as he shakes my hand. I manage a smile, a gaunt and desiccated grin that pries itself from cracked, swollen lips and a red-gummed cottonmouth.

I mutter a few words about my epic descent. The stuck rope. The sketchy half-length abseils on marginal gear. The jump. Then, between spasms of dehydration, I unwrap the bag’s contents. The glee of a child unwrapping a birthday present.

Perchance, January the first is my birthday. As I look up at the headwall and the summit above, I am thankful for the gift.

The water, that is.